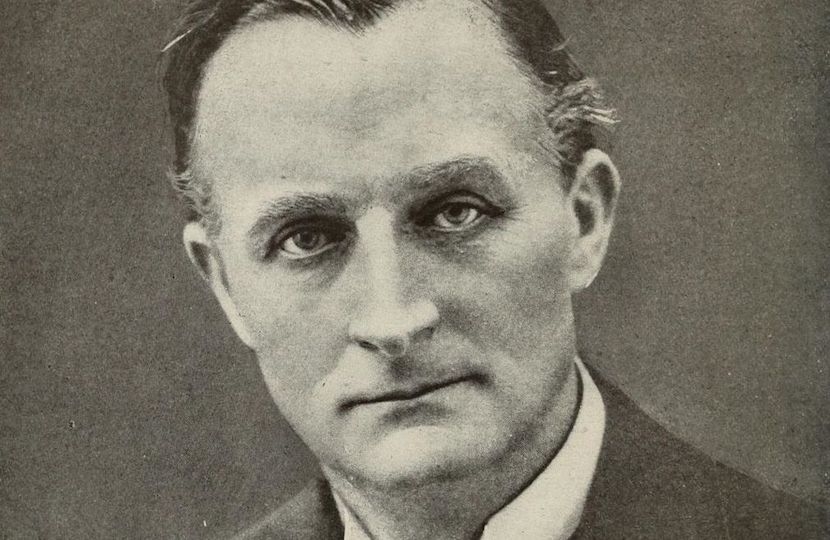

The analogy between the extinguishing of lamps and the end of peace in 1914 is well-known. It was made by Sir Edward Grey, the Foreign Secretary at the time. He is the subject of a fine new biography. Alistair Lexden’s review of the book is attached.

Statesman of Europe: A Life of Sir Edward Grey

By T. G. Otte

Allen Lane, £35

Sir Edward Grey (1862-1933) was Foreign Secretary from December 1905 to December 1916, eleven years to the very day, the longest unbroken stint that anyone has done in that great office, created in 1782. He is remembered as the man who failed to avert the First World War.

Its outbreak drew from Grey one of the best-known political quotations of all time. The famous words were spoken at the windows of the Foreign Office as the lamp-lighter went about his work at dusk on 4 August 1914. ‘The lamps are going out all over Europe. We shall not see them lit again in our lifetime.’

His critics said that if he had been a more accomplished politician the lamps might not have been extinguished. They saw him as a decent, but unimaginative English country gentleman, outmanoeuvred by the wily, sabre-rattling leaders of continental Europe. He continues to be denigrated . Andrew Adonis, my historian friend on the Labour benches in the Lords, regards him as ‘ arguably the most incompetent foreign secretary of all time.’

In this new biography, Professor T.G. Otte, an outstanding diplomatic historian, turns the tables on the critics. In 700 pages of clear, well-paced prose, he restores Grey’s reputation, drawing on over a hundred collections of private papers as well as on all the relevant official documents of the period.

Grey emerges from this door-stopper as a diplomatist of quite exceptional skill. He defused a series of acute crises in North Africa, the Near East and the Balkans which, without his dexterity, could well have led to catastrophe before 1914. While preserving ententes with France and Russia, he was careful to avoid firm alliances with anyone.

He played the great powers of Europe off against each other with great astuteness in the cause of peace. In Germany his talents were widely admired. In June 1914, just weeks before war broke out, he wrote that ‘ we are on good terms with Germany and we desire to avoid a revival of friction with her.’

His work was done behind closed doors, out of sight of ill-tempered parliamentary critics, who completely misjudged him. Thomas Otte’s detailed study of the documents which recorded his moves on the complicated diplomatic chessboard has at last revealed the true scale of his achievement.

It sometimes seemed as if he was married to the Foreign Office. His wife died shortly after he had taken up the post, plunging him into unending sorrow which long hours of work relieved. She had refused him sex since shortly after their wedding. Rumours abounded about his affairs with other women and the children he had fathered. Otte dismisses the tittle-tattle. He sees no reason to doubt that Grey had a blissfully happy, chaste marriage.

What went wrong in 1914? Austria’s decision to punish Serbia severely after the assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand roused fury in Russia, the self-appointed guardian of the Slav peoples. Only German intervention to restrain its impetuous Austrian ally could have saved the situation.

Grey used every conceivable diplomatic ploy with Germany right up to the moment when its armies moved against France, leaving Britain with no alternative but to fight. If it had been possible, Grey would have stopped the lamps going out, as Thomas Otte shows in this superb book.

Alistair Lexden is a Conservative peer and historian.