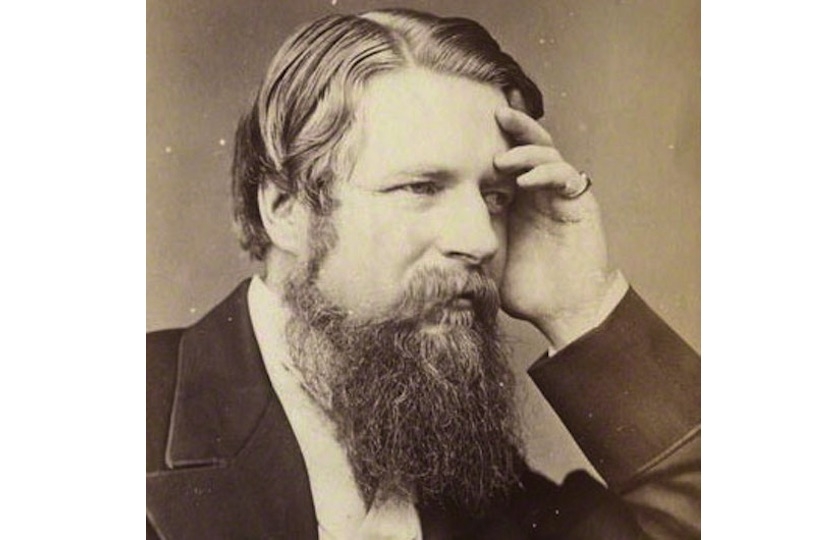

Few people today have even heard of Sir Stafford Northcote. He was a prominent late nineteenth century politician whose career ended in failure after nine years as Tory leader in the House of Commons from 1876 to 1885. In this article, Alistair Lexden reflects on his life and reveals the extraordinary chance survival of some of his diaries.

Sir Stafford Northcote, 8th Bt. FRS (1818-87) of Upton Pyne, near Exeter (a modest estate by Victorian standards of some 5,700 acres), became Tory leader in the Commons in 1876 when Disraeli, then aged seventy-two, went to the Lords for a quieter life. Disraeli died in 1881 while the Tories were in opposition, to be succeeded by the 3rd Marquess of Salisbury (“the great Lord Salisbury”, as he was later to be known) as leader in the Lords. From that point Northcote took first place in the affairs of the Conservative party in accordance with the convention of the time which provided that, if neither leader had been prime minister, the holder of the post in the Commons had precedence. The formal position of leader of the Conservative party did not come into being until 1922.

There is a colossal statue of Northcote in the Central Lobby of the House of Commons, seen by hundreds of visitors every day, but it seems to prompt no interest in his career. It is tempting to describe him as a forgotten Tory leader. That is undoubtedly true as far as most people are concerned ;like Austen Chamberlain, son of a famous father, who led the party briefly in 1921-22, he has no place in the public memory. He is, however, far from being forgotten by historians of the late nineteenth century. By them he is frequently recalled. In books on the period he appears as one of the most conspicuous victims ever of the cruel business of party politics.

After Disraeli’s death, this extremely able man with long experience of government and the House of Commons (he had been an MP since 1855) found himself in political circumstances to which he was completely unsuited. His party looked to him to assail Gladstone’s second ministry with unsparing ferocity. That was emphatically not Northcote’s style. He knew how to attack political opponents with effective arguments and had won golden opinions from Disraeli, but his tone was always measured and responsible.

Tory backbenchers grew restive. Some said that he showed undue respect for Gladstone whose private secretary he had been for eight years in the 1840s when the future People’s William had been the rising hope of the stern unbending Tories. The two men shared a passion for the classics (in which both held Oxford firsts) and religion. They had much in common. Northcote managed the most unusual feat of admiring both Gladstone and Disraeli.

Other Tory MPs provided the vicious partisanship from which their leader shrank. A small group with reputations to make stole the headlines with rude speeches about Gladstone and his policies. They were dubbed the Fourth Party. Sir Winston Churchill’s father, Lord Randolph, a young man in a hurry( he did not expect to live long), was the most zealous and ingenious of them in devising new ways of insulting the government.

Churchill did not stop there. He cheerfully insulted Northcote too. He conferred a humiliating nickname on him, “the goat”, and harried him mercilessly with an eloquent, mocking tongue. Memoirs of MPs active in the 1880s are full of tales of Churchill’s scurrilous wit employed at Northcote’s, as well as Gladstone’s, expense. Historians of the period have recycled them to lend colour to their narratives. I included a number in a short history of the Primrose League published in 2010, A Gift from the Churchills: The Primrose League,1883-2004. This organisation, the first to harness mass support for a political party in Britain, was founded to enable Churchill to take his effective brand of irresponsible politics from the Commons chamber to the country at large. Northcote was eclipsed on the wider public stage as well as at Westminster. Nevertheless, as the senior of the two party leaders, he felt bound to accept appointment as the League’s first Grand Master in 1883.

He was not ousted from the Commons leadership while the Tories remained in opposition, but the universal belief in 1881 that, as the senior of the two Tory leaders, he would be the next Conservative prime minister, vanished. After Disraeli’s death, Queen Victoria had led him to expect that she would send for him when the moment arrived; when it finally came in June 1885 the premiership was immediately entrusted to Lord Salisbury whose stock had risen sharply since 1881, thanks to his combative political style and Churchill’s support.

Northcote felt the humiliation acutely (who wouldn’t?), but bore it bravely in public. As happens occasionally, the historic post of First Lord of the Treasury was split from the premiership and given to him. He was in office but without power. To underline the point, he was kicked upstairs (the phrase seems to have been invented for him) as Earl of Iddesleigh.

An unkindly providence proved remorseless. In July 1886 he was given a real job as Foreign Secretary, but failed to satisfy Salisbury (himself one of the greatest of all Foreign Secretaries) and paid the price after only a few months in January 1887.It was the final humiliation. He called at No 10 to take leave of Salisbury and suffered a fatal heart attack in the prime minister’s presence. It seemed to shocked, guilt-ridden Tories a modern version of one of the Greek tragedies that Northcote had been so fond of quoting.

*

Here, then, is a man who has been defined for posterity by the failures of his last few years and the circumstances of his death. Little attention has been given to the many achievements of a long, productive career. Only the famous Northcote-Trevelyan report of 1853, which heralded the start of the modern civil service recruited on merit through examinations, tends to be held to his credit. Conspicuous by its absence is any recognition of Northcote’s contribution to social reform which many Tories believe wrongly was Disraeli’s exclusive domain. Industrial schools and reformatories for boys were his special interests.

No one has made any attempt to study his character, political beliefs, interests and personal relationships since 1890 when a biography in two volumes was published by a well-known Scottish writer and poet of the time, Andrew Lang. It is laden with Victorian pieties and attempts no serious evaluation of its subject’s work. There is no route to a proper appreciation of Northcote through its pages. Lang was ill-suited to the task. He detested politics, but needed the money.

Northcote, the tragic Tory leader, awaits an adequate biographer. There is abundant material in the 52 volumes of the Iddesleigh papers, deposited many years ago in the British Museum and now in the British Library. They include a set of diaries, vital for the elucidation of character and the understanding of political motive, which Northcote kept intermittently between 1866 and 1883.

Northcote’s grieving widow, Cecilia, mother of their ten children, seems to have been unwilling to entrust the diaries themselves to his biographer, even though these records of a blameless life almost certainly contained nothing that was potentially embarrassing. Devoted widows tend to take no risks with the reputations of their beloveds. Typescript copies were prepared for Lang who included large extracts in his biography, but felt no compunction about amending them freely as he went along. Severely mangled versions of material in the typescripts ended up in print.

Just one portion of the typescript diaries in the Iddesleigh papers, recording a political visit to Ulster in October 1883, has been published in an accurate edition—by me, as it happens, in a singularly obscure place, the Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy. It has, however, got itself by some means on to the internet and can be found quite readily.

What happened to the original diaries? The current Lord Iddesleigh offers no clues. It seems almost certain that most of them no longer exist. By an extraordinary chance, however, four, all relating to visits abroad, ended up safely in the possession of a total stranger. At some point before the Second World War, the four, bound up together in two small blue volumes, found their way to the Law Courts in the Strand. It is impossible to establish how they came into the clutches of lawyers; Northcote’s successors do not seem to have been involved in litigation to which they would have been relevant. All that is known is that a Clerk in the Chancery Division, named Stanley Holloway(no relation of the famous entertainer), who loved collecting curious objects, spotted them among the litter at the Courts and took them home. He later recorded that he found them “in a heap of old books and waste paper during a ‘waste paper drive’ at the Law Courts during the Second World War”. Their current owner is his daughter.

The diaries record what a prominent English politician in the late nineteenth century made of parts of the world of which few at Westminster then had any first-hand knowledge. Northcote journeyed to more places outside Europe than any other Tory of cabinet rank at that time. In the “Holloway diaries” he has left us detailed accounts of the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, of the newly formed Canadian Confederation which he visited in 1870 to arrange the transfer of vast territories from the Hudson’s Bay Company (of which he was chairman) to the Canadian government, and of the United States under President Grant with whose ministers he held long discussions in 1871 as part of a commission sent to settle a series of disputes which had poisoned Anglo-American relations since the Civil War. The fourth of these diaries records his impressions of the Mediterranean during a yachting holiday in 1882.

Perhaps Northcote’s vivid tales of travel will help to kindle interest in this tragic Tory leader. Their current owner has decided to add them to the Iddesleigh papers. As the result of a remarkable chance survival, the set of diaries at the British Library can now be made as complete as is possible in the year which marks the 130th anniversary of the diarist’s death.

Alistair Lexden

May 2017