Neville Chamberlain is the principal focus of Alistair Lexden’s historical work this year.

The following article, published in the August/September issue of The London Magazine, supplements the brief assessment of the relationship between Chamberlain and Churchill in Alistair’s recent lecture on Chamberlain broadcast on BBC Parliament on 14 July (see below).

***

The much-lauded recent film Darkest Hour portrays Churchill perhaps more powerfully than ever before on the screen as a man of destiny, uniquely qualified to save Britain and the world from Nazi tyranny. The man in whom the country expected to repose its destiny in May 1940, Lord Halifax, is depicted as a cringing appeaser intent on blocking Churchill’s great fight for freedom and selling out to Hitler.

In reality most Tories, the Labour Party and King George VI were looking forward to a Halifax premiership. Churchill only got to No 10 because Halifax turned down the glittering prize, as Nicholas Shakespeare shows in his brilliant, thoroughly researched book, Six Minutes in May, published last year.

The film’s portrayal of Halifax is a travesty, though it is true that, after rejecting appeasement in 1939, the Foreign Secretary proposed at the end of May 1940 that the possibilities of a negotiated peace should be explored.

Neville Chamberlain is treated rather more sympathetically. He is shown as retaining considerable political power after his loss of the premiership. That is correct; most Tory MPs continued to place their trust in him. What is not correct is the film’s imputation that for some weeks Chamberlain treated his successor as being on probation, finally giving him full endorsement in a dramatic scene. In fact the two men were at one throughout.

Patrick Donner, a Second World War RAF pilot and Tory MP, wrote in his memoirs: “must not the final verdict be that Neville Chamberlain and Winston Churchill between them saved this country? Neither statesman would have achieved our salvation without the other”.

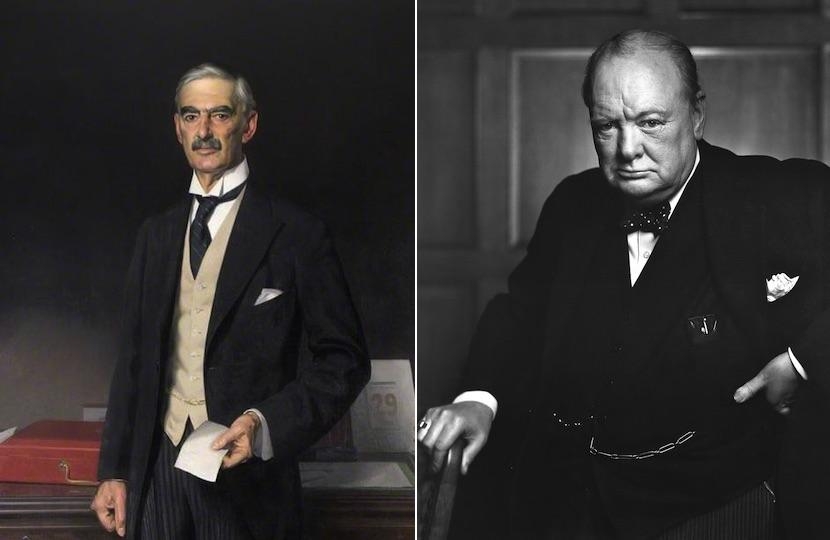

The same view was expressed movingly by one of Chamberlain’s Birmingham constituents, a Mrs Hodge, who wrote to him on the day he died in November 1940, telling him that “you saved the life of our country and we will always think of you with deep and everlasting gratitude”. She added a PS: “I have a portrait of you and Mr Churchill side by side on my mantelpiece.”

Everyone remembers that, during his “wilderness years” in the 1930s, Churchill fiercely criticised Chamberlain for failing to equip the country for the world war that he confidently (and correctly) predicted. In the first volume of his later, enormously successful account of the war—over half a million copies were sold—Churchill presented his criticisms as unarguable facts. People believed what the nation’s hero said.

But it was not true. In May 1938, four months before the Munich agreement, Chamberlain told the annual Conservative Women’s Conference that “we have to make ourselves so strong that it will not be worth while for anyone to attempt to attack us”. His rearmament programme was on a massive scale. Professor David Dilks, a leading expert on the period, has pointed out that under Chamberlain “Britain was spending between 40 and 50 per cent of GDP on defence”—far more than under any previous government in peacetime.

The huge sums were well spent, too— for example, on radar and on the fighter planes, Hurricanes and Spitfires, that saved us in the Battle of Britain. Six months before Munich, Churchill wrote to Chamberlain, telling him that Britain had little need of them; we should just concentrate on producing more and more bombers. Fortunately, his advice was disregarded.

Chamberlain’s extensive preparations for war enabled the two men to work together closely and successfully after conflict had broken out. From September 1939 to May 1940 Churchill served under Chamberlain as First Lord of the Admiralty; from May 1940 until shortly before his death in November, Chamberlain served under Churchill as Lord President of the Council.

Chamberlain chaired the war cabinet in Churchill’s absence; he opposed Halifax’s peace proposals in late May 1940; he undertook a huge burden of work until the onset of death from cancer compelled him to resign.

Chamberlain wrote: “Winston has behaved with the most unimpeachable loyalty. Our relations are excellent and I know he finds my help of great value to him”. Churchill reciprocated: “I have received a great deal of help from Chamberlain. His kindness and courtesy to me in our new relations have touched me. I have joined hands with him and must act with perfect loyalty.”

Churchill was distraught when Chamberlain died. “What shall I do without poor Neville?”, he said. “I was relying on him to look after the Home Front for me.” It had been a perfect partnership with Churchill concentrating on strategy and negotiations with allies while Chamberlain, perhaps the greatest administrator of his age, ran the country’s internal affairs.

When the House of Commons met in Church House on 13 November 1940 to pay tribute to Chamberlain, Churchill’s eloquence was at its height. “He had a precision of mind and an aptitude for business which raised him far above the ordinary levels of our generation. He had a firmness of spirit which was not often elated by success, seldom downcast by failure and never swayed by panic…He met the approach of death with a steady eye. If he grieved at all, it was that he could not be a spectator to our victory, but I think he died with the comfort of knowing that his country had, at least, turned the corner.”

Five years passed before Churchill started work on his self-serving war memoirs. The memory of the perfect partnership had faded. He attacked Chamberlain again as he had during the “wilderness years”. The truth about their relationship, and the part it played in saving our country, was lost.

_______________

This is an extract from a lecture entitled “Neville Chamberlain: Myth and Reality” delivered by Alistair Lexden at a meeting of members of the Carlton Club (which has a fine portrait of Chamberlain by Sir James Gunn) on March 13.

BIBLIOGRAPHY. Arthur Bryant(ed.), In Search of Peace: Speeches (1937-1938) by the Right Honourable Neville Chamberlain M.P. (1938). Alistair Cooke, ‘Neville Chamberlain’s Private Army’ in Alistair Cooke (ed.), Tory Policy-Making: The Conservative Research Department 1929-2009 ( 2009). Winston Churchill, ‘Neville Chamberlain’ in Angela Huth (ed.), Well-Remembered Friends: Eulogies on Celebrated Lives (2004). David Dilks, ‘The Ascendancy of Chamberlain’ in Lord Butler (ed.), The Conservatives: A History from their Origins to 1965 (1977). Robert Self, Neville Chamberlain: A Biography (2006). Nicholas Shakespeare, Six Minutes in May: How Churchill Unexpectedly Became Prime Minister (2017).